Forests, Scorchers and Bears: Early Cycling in Seattle

By Bill Thorness, BikingPugetSound.com

Cycling from downtown Seattle to Lake Union or Lake Washington today is a matter of simply choosing a route and having some stamina for the hills. But when Seattle was a young city in the 1890s, it meant blazing a trail through heavy forest, making the slow trek with virtually no services, and possibly being greeted by a bear … or Seattle’s first bike cop.

The history of cycling in early Seattle is a story of trailblazers, entrepreneurs, fashion and fad. Bikes came to the area as early as 1879, the year the first chain-driven bicycle was invented. It was well before there were any smooth roads upon which to ride. Far from the comfortable, well-balanced steeds of today, early Seattle bikes were of the “penny farthing” or “highwheeler” variety, distinguishable by their large front wheel and tiny rear one. The machine had a propensity to throw riders off over the front wheel, which was even then called “doing a header.”

In 1883 the pneumatic-tired “safety bicycle” arrived, and in the few years following, the use of bikes as adult recreational vehicles took off.

In 1883 the pneumatic-tired “safety bicycle” arrived, and in the few years following, the use of bikes as adult recreational vehicles took off.

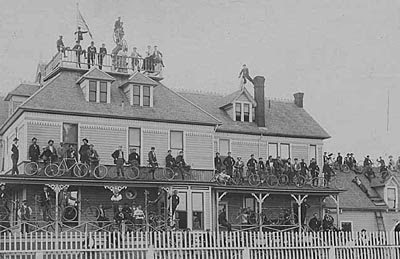

Queen City Bicycle Club on a visit to the Van Devanter home

in Kent, Washington (Image # 296).

Courtesy White River Valley Museum, Auburn.

Bike-building explodes

The clamor for bicycles swept the nation and European countries in the 1890s, and Seattleites got into the trend. Production of bicycles nationwide had been perhaps 200,000 in 1880, but by 1890 it would be more than one million.

In Seattle, dozens of bicycle businesses cropped up. There were more than 40 firms selling bikes during the 1890s, including the Bon Marche and the Bicycle Sanitarium. On a six-block section of Second Avenue between Marion and Pike there were 23 bicycle shops, including three bicycle builders. Early Seattle models included:

- “The Rainier,” built by A.J. Williams in 1898

- “The Queen City Bicycle”

- Built-to-order bikes from the Cyclone Cycle Company in Fremont

- A “Roadster” and a “Special” built by Piper and Taft

- “The Spinning,” built by F. M. Spinning

Unusual bikes were seen around town too. In 1895, the first tandem arrived in Seattle; in 1896, a triplet arrived; and in 1901, a quadricycle. There were pedaled contraptions seating up to 15 people, and a sextet was reportedly spotted in 1896, but there are no reports of anyone riding it. (To see a great selection of historic bikes from many eras, visit the collection at Classic Cycles on Bainbridge Island.)

Cycling lore of the era comes largely from the Argus newspaper, which had a cycling column running weekly from 1894 to 1903, the heyday of the cycling craze.

Blazing the paths

Early adopters of the bicycle in Seattle initially had nowhere to ride. In 1894, paver bricks were laid down on one city block, and by 1896 there was one mile of paved street. Cyclists took up the cause for smooth riding and formed the Queen City Bicycle Club, whose members lobbied for better roads. They also started building bike paths.

The first path went from downtown Seattle and along the east side of Lake Union, and was 2.5 miles long. It opened on Sept. 19, 1896, with 200 cyclists in a parade with lanterns hanging from their bikesNext to come was a 10-mile cinder path to Lake Washington, which opened on June 19, 1897, using Lakeview and Interlaken boulevards to reach Madison Park.

Two women on the Lake Washington Cycling Path,

between 1900 and 1903.

Courtesy Museum of History & Industry, Seattle.

Two women on the Lake Washington Cycling Path,

between 1900 and 1903.

Courtesy Museum of History & Industry, Seattle.

Along the path a“halfway house” was built, which served breakfast and lunch for cyclists on their day trip to the lake. This comfort stop was located between Roanoke Park, on the northwest edge of Capitol Hill, and what is now 23rd Ave. E.; it was mostly likely on the west edge of the ravine through which Interlaken Boulevard runs.

The next year, the city extended the Lake Washington Path to Leschi, and the Lake Union Path to Green Lake. A path to Fort Lawton in Magnolia was created, and another path linked Fremont and Ballard.

Development of the early paths was championed by Assistant City Engineer George F. Cotterill, who was also active in the bicycle club. He walked many of the routes to survey them, then supervised their construction. Cotterill later became a state senator, and held a term as mayor of Seattle.

Cyclists didn’t have to venture far along these paths to escape the city noise and crowds. The Lake Washington Path reportedly plunged riders into deep forest, where an occasional black bear encounter was to be had. The Magnolia path bisected farmland, and the trail conditions were often poor due to cattle grazing along its edge. Further, the cavalry soldiers from Fort Lawton would ride their horses along the trail – a combination of problems that eventually led to the path’s abandonment.

Cyclists didn’t have to venture far along these paths to escape the city noise and crowds. The Lake Washington Path reportedly plunged riders into deep forest, where an occasional black bear encounter was to be had. The Magnolia path bisected farmland, and the trail conditions were often poor due to cattle grazing along its edge. Further, the cavalry soldiers from Fort Lawton would ride their horses along the trail – a combination of problems that eventually led to the path’s abandonment.

But even out in the wilds of what is now Madison Park and Leschi, a rider could not escape the long arm of the law. The path was patrolled by A.C. Deuel, Seattle’s first bike cop, who would arrest speeders (called “scorchers”) and ticket riders who were passing on curves or riding unlicensed bicycles. He also would fill gopher holes on the path and chase off cattle.

Off to the races

Cycling for fun and exercise was only part of the biking trend; people loved to watch bike races. As the bicycle proliferated on the streets, so too did the racetracks. The first races were held at a horseracing track in south Seattle. In 1888, a series of four cycling races was part of the July 4th entertainment. There was a race for new riders (less than one year), experienced riders (more than one year), youth under 17, and a five-mile race between a cyclist and a horse. The biker dropped out after four miles, citing the track conditions.

By 1895, the Seattle Bicycle Club had its own track, located near Woodland Park, probably in the vicinity of 58th Street and Phinney Avenue North. Grandstands seated 2,000 people, and a clubhouse had lockers, showers, and stalls for bike storage. The track was surrounded by an eight-foot fence, and racers came from as far away as Victoria, B.C. and Portland to compete in the Sunday events, which cost 25 cents for spectators.

In August of 1895, the YMCA-sponsored Triangle Bicycle Club opened a track on Capitol Hill between Cherry and Jefferson streets, bordered by 12th and 14th avenues, roughly the location of Seattle University’s playfields today. It featured night racing under electric lights.

Two indoor tracks were also drawing crowds. One downtown between 3rd and 4th avenues on Union was reportedly used only once, for a traveling women’s six-day race. The Cycle Palace Track, opening on July 4, 1901, was modeled after tracks in France. It was located on the edge of downtown, bordered by Howell, Boren, Minor and Olive.

The waning popularity of bicycling could be seen in the racing trend, which dropped after the turn of the century. Track racing ended in 1903, the same year the Argus folded its cycling column.

Historians often cite the rise of the automobile as the reason for cycling losing its luster, and some say motor vehicle technology relied heavily on the development of the bicycle. Such innovations as lightweight steel, pneumatic tires, wheel bearings and even gearing were adapted for use in cars. And those bike paths in Seattle became some of the city’s most scenic byways. Those are a couple of great reasons from history that cyclists and motorists should continue to “share the road.”

It would be the middle of the 20th Century before cycling would catch on again.

More to come: Look for more recent Seattle cycling history, including the development of the modern trails system, on BikingPugetSound.com in the near future.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Frank B. Cameron for an extensive history printed in 1982 that appeared, in part, in “The Wheelmen” magazine; Peter Lagerwey, City of Seattle Department of Transportation Bicycle and Pedestrian Program; Paul Dorpat’s excellent history series; HistoryLink.org; and the Museum of History and Industry, Seattle.

Looking forward to joining Seattle's first Tweed Ride! Great article on the history of cycling in Seattle, thanks for sharing it.

ReplyDelete